Emerging from the Blue Mountains in Eastern Oregon, Lookingglass Creek travels through the Umatilla National Forest then through private land before entering the Grande Ronde River, a tributary of the Snake River. With five major tributaries—Lost Creek, Summer Creek, Eagle Creek, Little Lookingglass Creek, and Jarboe Creek—the Lookingglass Creek watershed provides essential spawning habitat for spring chinook salmon.

Background

Nearly all spring chinook spawning occurs in Lookingglass Creek and its largest tributary, Little Lookingglass Creek. The native spring chinook population in the Lookingglass Creek basin once supported significant tribal and sport fisheries. Historical redd count data from the 1950s-1970s indicate that spring chinook abundance typically exceeded 1,000 adults.

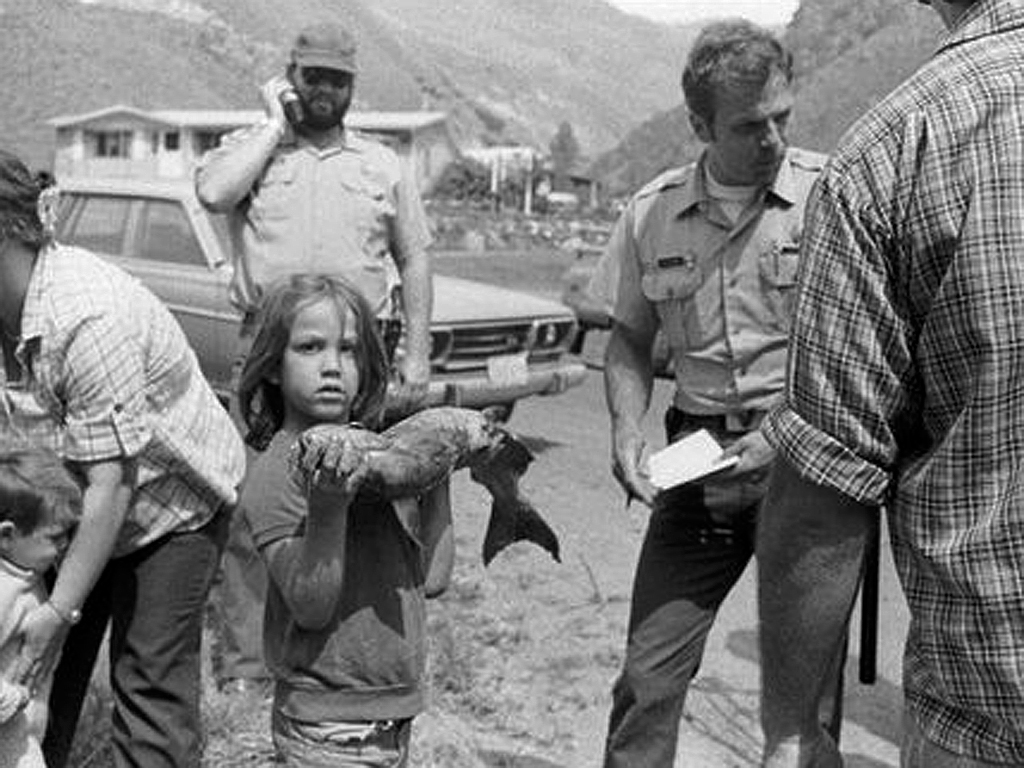

The completion of lower Snake River dams in the 1970s as well as the construction of the Lookingglass Hatchery and weir in 1982, however, led to the extirpation of the native population of spring chinook in the watershed. Still Lookingglass Creek had relatively unaltered habitat that could support spawning salmon.

Bringing Fish Back to the Habitat

The loss of this population and the associated fishery prompted the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation to begin an effort to reestablish a spring chinook population in the watershed.

In 1992 the tribe began a reintroduction program. From 1992 to 1999, a non-endemic (non-local) Rapid River, Idaho stock with a history of hatchery domestication was introduced to reestablish a spring chinook population. The weir and trap at the hatchery and outmigrant trap allowed for precise monitoring of fish in and fish out. Intensive monitoring of natural production occurred throughout the 1960s, which provided benchmark productivity data for biological comparisons.

Broodstock Differences?

Performance measures for returning adults of the Rapid River stock were similar to the endemic stock across all metrics evaluated (redd distribution, spawn timing, adults per redd, outmigrants per redd, outmigration timing and survival, and parent/progeny ratios).

After objections from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries and rules prohibiting use of the non-local Rapid River stock, the Umatilla tribe was obliged to restart the reintroduction program with an inbasin stock. In 1999 the stocking of Rapid River juveniles ceased, and for the next several years the tribe had to block passage of all returning adults, causing the upstream population to again go extinct.

In 2001 the tribe reintroduced juveniles produced from a recently established Catherine Creek stock, a nearby Grande Ronde River tributary. In 2004 the first year that adults from the new Catherine Creek stock returned to the basin and passage of fish upstream was again permitted.

Beginning in 2007, the first adult progeny from natural spawning of the 2004 broodyear fish returned. Supplementation of the new population continues—using a mix of natural- and hatchery-origin broodfish—with the intent of promoting the creation of a naturalized Lookingglass stock.

Information acquired through the monitoring program permits performance measure comparisons of the new Catherine Creek stock, as well as the prior Rapid River stock, to the endemic fish (shown in the table below). These results and others indicate striking potential for success of hatchery reintroduction and supplementation programs for spring chinook.

Productivity measures for the endemic and the two introduced stocks of spring chinook in Lookinglass Creek

(Outmigrants are juvenile fish counted as they leave their natal stream on their way to the ocean.)

| Stock | Brood year |

Redds | Outmigrants Produced |

Outmigrants per Redd |

| Endemic | 1965 | 99 | 33,437 | 338 |

| 1966 | 279 | 55,315 | 198 | |

| 1967 | 120 | 31,036 | 259 | |

| 1968 | 133 | 29,076 | 219 | |

| 1969 | 276 | 33,148 | 120 | |

| Rapid River Stock |

1992 | 49 | 8,715 | 178 |

| 1993 | 132 | 46,536 | 353 | |

| 1994 | 40 | 6,388 | 160 | |

| 1996 | 24 | 14,625 | 609 | |

| 1997 | 24 | 13,330 | 555 | |

| Catherine Creek Stock |

2004 | 49 | 16,344 | 334 |

| 2005 | 29 | 11,500 | 397 | |

| 2006 | 28 | 12,502 | 447 | |

| 2007 | 32 | 7,796 | 244 | |

| 2008 | 104 | 59,942 | 576 |

Lookingglass Cr. watershed

Location

Genetic resources

A contentious past

For more information

Lookingglass Hatchery Success Brochure.