photo: Jeffrey Rich

In 1930, the annual Snake River fall chinook run was around half a million fish annually. In 1990, only 78 returned to Lower Granite Dam, the last of the lower Snake River dams before entering Idaho. It appeared that this run would soon go extinct. To prevent that from happening, the Nez Perce Tribe, in coordination with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife implemented a program that has brought this run back from the brink of extinction.

Background

In the early 1900’s, Snake River fall chinook were widely distributed from the mouth of the river upstream to Shoshone Falls in southern Idaho, more than 900 miles from the ocean. As late as the 1930’s, fall chinook returns in the Snake River numbered 500,000 adults.

The construction of dams on the Snake River, beginning with Swan Falls in 1901 and continuing with the Hells Canyon Dam Complex in the 1950’s and Lower Snake River dams in later years, eliminated or severely degraded 530 miles – or 80% – of the historical habitat. The most productive of that habitat was upriver from the site of Hells Canyon Dam, which has no fish passage. A precipitous decline of Snake River fall chinook followed with only 78 wild adults observed at Lower Granite Dam in 1990.

NOAA’s response to the listing of Snake River fall chinook under the Endangered Species Act in 1992 threatened the tribal fall season fishery, the remaining tribal commercial fishery. In 1994, NOAA sought to restrict the tribal fishery under the ESA setting the stage for a potential landmark conflict between tribal treaty rights and the ESA.

- NOAA’s goal: cut the tribal fishery to increase the fall chinook at Lower Granite Dam by 24 fish.

- The tribes’ goal: fairly allocate the burden of conserving the salmon among all sources of mortality, establish a connection between hatcheries, and harvest while developing a program that would benefit Snake River fall chinook and allow the tribes to exercise their treaty reserved fishing rights.

With the stage set, U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm Marsh warned the parties that while he was willing to hear this case, not everyone would like the outcome. The tribes were risking their treaties signed in 1855 and the federal government was risking the Endangered Species Act. Taking his warning to heart, both parties began negotiating.

The agreement reached by the parties led to a cutting-edge hatchery program that allows the Nez Perce Tribe to supplement natural chinook populations with hatchery-reared fish of the same stock. The agreement spurred the development and issuance of Secretarial Order #3206 by the secretaries of Interior and Commerce, which seeks to harmonize the federal government’s duties to the tribes and the ESA.

Supplementation

The increased returns are the result of a Nez Perce tribal initiative to supplement existing Snake River fall chinook with biologically appropriate hatchery-reared fish to increase naturally spawning runs. Started in 1995, the Bonneville Power Administration agreed to fund this program that relied on a technique that was controversial at the time. The program now enjoys broad regional support for supplementation from numerous federal and state agencies.

The details of the Snake River Fall Chinook Program were refined in 1995 through U.S. v. Oregon processes, when the four Columbia River treaty tribes reached an agreement with state and federal agencies to begin supplementation of Snake River fall chinook above Lower Granite Dam. The development of numerous rearing and acclimation facilities in the Snake River Basin as well as the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery was essential to the implementation of the program. The tribes secured the initial funding for the program through the U.S. Congress. In 1996, Congress instructed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to construct acclimation facilities under the Lower Snake River Compensation Plan. Today the Nez Perce Tribe Department of Fisheries Resources Management operates and maintains three acclimation facilities at Captain John Rapids, Pittsburgh Landing and Big Canyon under the LSRCP in addition to the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery.

Together, these facilities release approximately 450,000 yearling fall chinook and 2.8 million sub-yearling fall chinook as part of a broader program that releases 5 million juvenile fish back into the system. These releases into the Snake and Clearwater rivers have increased the number of adult fall chinook returning above Lower Granite Dam but more importantly, they have increased the number of wild fish returning to the Snake River, since most of the out planted fish spawn naturally, producing wild offspring.

The major Snake River sub basins that are part of this restoration effort are indicated in red.

Snake River salmon once returned to the base of Shoshone Falls in southern Idaho, more than 900 miles from the ocean.

Image: Thomas Moran, Shoshone Falls on the Snake River (detail), 1900, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Located on the banks of the Clearwater River in Idaho, the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery Complex began operations in 2003. This is the main facility supporting the Clearwater River component of the Snake River fall chinook program. At the facility, the tribe strives to preserve the genetic integrity of affected fish populations while enhancing harvest opportunities for treaty Indian and non-Indian fishers. The Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery Complex uses several semi-natural rearing techniques to encourage hatchery-reared fish to behave like their wild counterparts.

Snake River Fall Chinook Acclimation Sites

Captain John Rapids Outplanting Site

Around 700,000 sub yearling fall chinook are outplanted at this site on the Snake River.

Around 700,000 sub yearling fall chinook are outplanted at this site on the Snake River. Pittsburg Landing Outplanting Site

Around 400,000 subyearling fall chinook are outplanted at this site on the Snake River each year.

Around 400,000 subyearling fall chinook are outplanted at this site on the Snake River each year. Big Canyon Creek Outplanting Site

Around 500,000 subyearling fall chinook salmon are outplanted at this site next to the Clearwater River each year.

Around 500,000 subyearling fall chinook salmon are outplanted at this site next to the Clearwater River each year. Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery Acclimation Ponds

500,000 fall chinook subyearlings are acclimated and released into the Clearwater River from the acclimation ponds at the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery each year.

500,000 fall chinook subyearlings are acclimated and released into the Clearwater River from the acclimation ponds at the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery each year.North Lapwai Valley Acclimation Site

Around 500,000 fish are acclimated and released at North Lapwai Valley into Lapwai Creek about 1/2 mile upstream from the Clearwater River.

Around 500,000 fish are acclimated and released at North Lapwai Valley into Lapwai Creek about 1/2 mile upstream from the Clearwater River.Luke's Gulch Acclimation Site

200,000 subyearlings from the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery are transported here for acclimation and release into the South Fork Clearwater River each year.

200,000 subyearlings from the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery are transported here for acclimation and release into the South Fork Clearwater River each year.Cedar Flats Acclimation Site

The Cedar Flats acclimation site releases 200,000 subyearlings from the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery into the Selway River each year.

The Cedar Flats acclimation site releases 200,000 subyearlings from the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery into the Selway River each year.Sweetwater Springs Acclimation Site

400,000 fall chinook destined for the Luke’s Gulch and Cedar Flats facilities are temporarily reared at the Sweetwater Springs facility for up to two months before being transferring for final acclimation and release.

400,000 fall chinook destined for the Luke’s Gulch and Cedar Flats facilities are temporarily reared at the Sweetwater Springs facility for up to two months before being transferring for final acclimation and release.

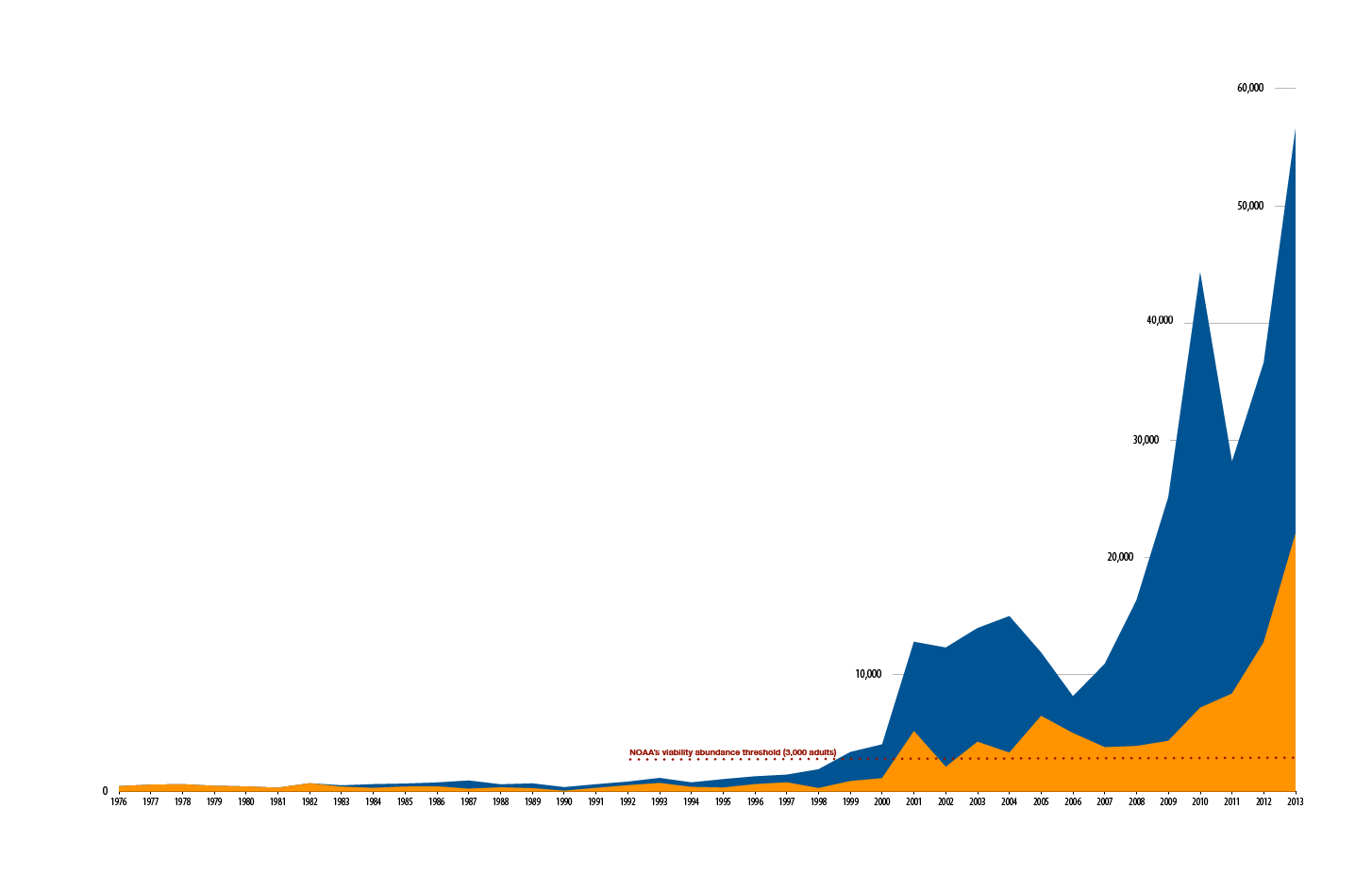

Snake River Fall Chinook Counts at Lower Granite Dam

Wild

Hatchery

Total

1990

2015

We must continue to do everything we can to ensure the fish runs continue on this path toward a healthy, self-sustaining population capable of supporting well-managed tribal and non-tribal fisheries.

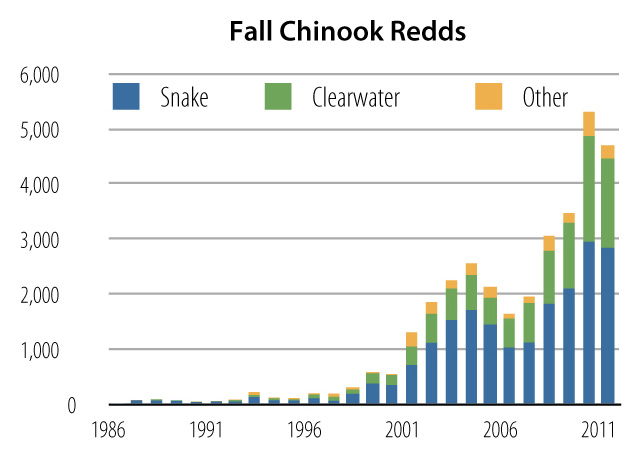

The Road to Salmon Recovery

Adult fall chinook salmon returns have increased from less than 1,000 adults to Lower Granite Dam annually from 1975-1995 to a record count of more than 55,000 in 2013. In 2014, 25 years after the fall chinook count was only 78 fish, 59,300 fish passed the dam. Over 16,000 of these fish were natural origin, making up 28 percent of the year’s run.

NOAA has discussed an abundance goal of 2,500-3,000 natural-origin Snake River fall chinook for potential de-listing even though no formal recovery criteria have been established. The progeny of the Fall Chinook Acclimation Program and the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery spawners are considered listed under the Endangered Species Act when they return to spawn. The tribal program will aid in ESA recovery of the Snake River fall chinook while helping support Snake River, Columbia River, and ocean fisheries.

A shared success

The continued increase in returns of Snake River fall chinook allowed co-managers to open a fall chinook fishery in the Snake River in 2009. This was the first fall chinook fishery on the Snake River in 35 years and the fishery has occurred each year since.

“The success of the Snake River fall chinook is something this region can really be proud of,” said Paul Lumley, Executive Director for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. “Over the last 20 years, we’ve moved from the courtroom to supporting fisheries while putting a substantial number of retuning adults on the spawning grounds. This type of program should be replicated throughout the Columbia River Basin, not limited.”

Although there has been a significant increase in the number of fall chinook adult returns and redds as a result of tribal efforts, the productivity of natural and hatchery origin fall chinook returns is still being evaluated. In the meantime, local Indian and non-Indian fishers in the Snake River are experiencing a bounty unseen since the construction of the dams

Download a print version of this story here. ![]() (3.5MB)

(3.5MB)