Last year, a record 56,000 Snake River fall chinook passed Lower Granite Dam. Making this even more impressive is that only 20 years ago, these fish were on the brink of extinction. This is one of the greatest achievements of Columbia River salmon restoration efforts to date, and the fact that it is the result of a massive tribal effort makes the accomplishment all the sweeter.

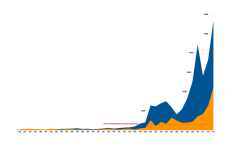

Total hatchery (shown in blue) and wild (shown in orange) Snake River fall chinook salmon counts at Lower Granite Dam. The year the Snake River Fall Chinook Recovery Program began in 1996.

In the early 1900’s, Snake River fall chinook were found from the mouth of the Snake River upstream to Shoshone Falls in southern Idaho more than 900 miles from the ocean. As late as the 1930’s, annual fall chinook returns in the Snake River numbered a half million adults.

The construction of dams on the Snake River eliminated or severely degraded 530 miles (80%) of the historical habitat. The most productive of that habitat was upriver from Hells Canyon Dam—a dam with no fish passage. This resulted in a steep decline of Snake River fall chinook. Annual adult fall chinook returns were fewer than 1,000 adults at Lower Granite Dam from 1975 to 1995. In 1990, only 78 wild adults passed the dam.

The Nez Perce Tribe began implementing its recovery program in 1995 using existing hatcheries and facilities. This showed some signs of success, but they knew that what the program needed was a dedicated facility to raise the wild salmon to outplant throughout their range. After a long and often frustrating 10-year process, the Nez Perce Tribe finally won approval to build a cutting-edge hatchery to supplement natural chinook populations with hatchery-reared fish of the same stock. The Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery was completed in 2005. (pictured above). This facility now produces about 450,000 yearling and 2.8 million sub-yearling fall chinook smolts that are released each year into the Clearwater and Snake rivers.

The Nez Perce Tribe began implementing its recovery program in 1995 using existing hatcheries and facilities. This showed some signs of success, but they knew that what the program needed was a dedicated facility to raise the wild salmon to outplant throughout their range. After a long and often frustrating 10-year process, the Nez Perce Tribe finally won approval to build a cutting-edge hatchery to supplement natural chinook populations with hatchery-reared fish of the same stock. The Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery was completed in 2005. (pictured above). This facility now produces about 450,000 yearling and 2.8 million sub-yearling fall chinook smolts that are released each year into the Clearwater and Snake rivers.

After twenty years of barely hanging on, the run began to increase once the Nez Perce recovery program started. The number of adult fall chinook returning above Lower Granite Dam has increased, but more importantly, the number of wild fish returning to the Snake River has inceased, too. Most of the outplanted fish spawn naturally, producing wild offspring. An estimated 21,000 (38%) of last year’s run were wild fish, setting a new record since the construction of Lower Granite Dam in 1975.

In 2009, the higher returns of Snake River fall chinook allowed co-managers to open the first fall chinook fishery in the Snake River in 35 years. This fishery has occurred each year since then.

This road to recovery was long and hard. The only reason it even happened is because of intertribal cooperation and intense pressure from tribal leadership. The lone tribal voices, along with support from Bonneville Power Administration prevailed against strong opposition from Washington Fish and Wildlife, Idaho Fish and Game, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA Fisheries, and Oregon Fish and Wildlife. Today, these agencies are cooperating with tribal restoration efforts, but in the early 1990’s, they had pulled out all the stops to keep the Nez Perce Tribe from implementing its plan. Here’s to tribal dedication and perseverance.