Pacific Lamprey

A Cultural Resource

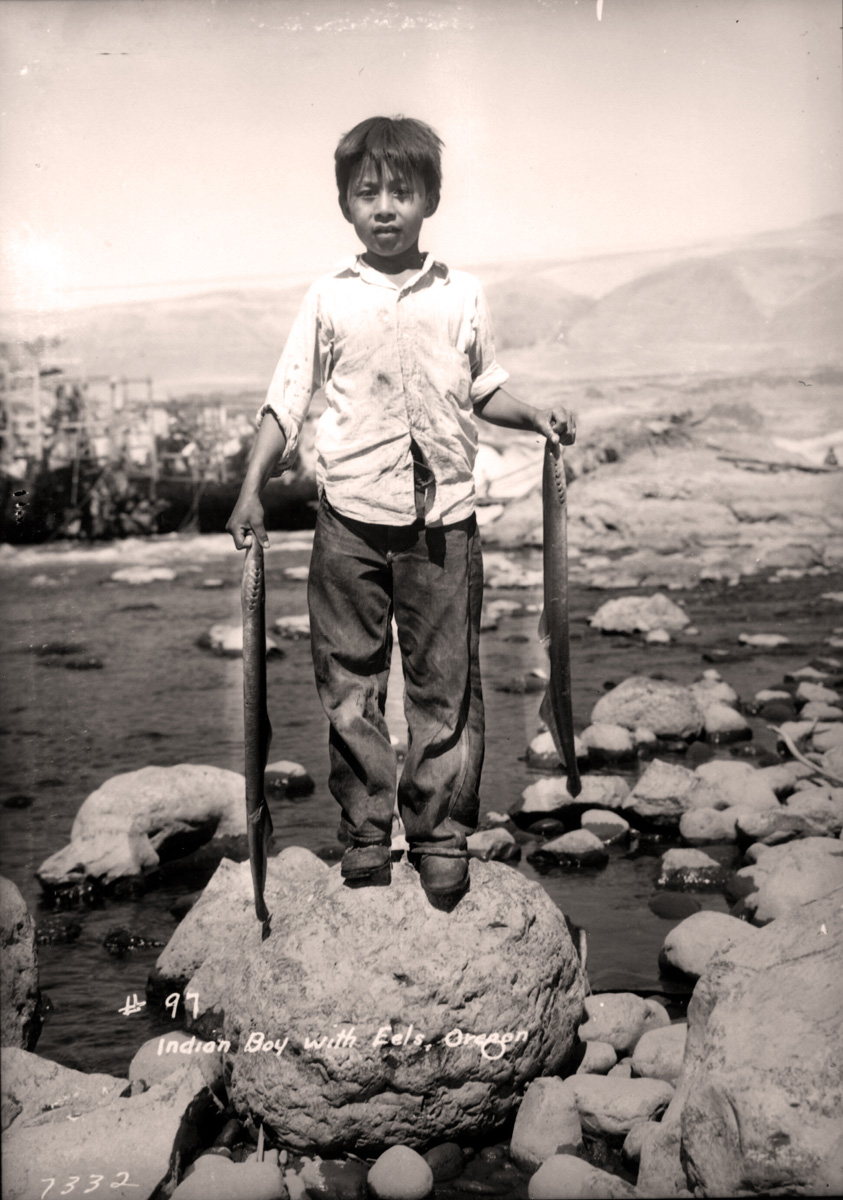

The Pacific lamprey provided an important source of food for the tribes of the Columbia River Basin, who prized them for their rich, fatty meat. They were served alongside salmon at tribal feasts and celebrations. While generally considered a trash fish by the non-tribal population, the tribes have attempted to maintain their connection to the lamprey. As the numbers of returning lamprey declined throughout the Columbia River Basin, the few places that lamprey remained abundant became even more precious—most notably at Willamette Falls at Oregon City, Oregon.

At Willamette Falls, where there continues to be a harvestable run of lamprey, tribal fishers gather each year to collect lamprey for feasts and dinners, continuing an age-old tradition.

My great aunt was a medicine woman, and she would collect the fat that would drip off an eel as it was cooking over a fire. She would store the fat in a small bottle and use it for oil in lamps and for medicines. My great aunt was a medicine woman, and she would collect the fat that would drip off an eel as it was cooking over a fire. She would store the fat in a small bottle and use it for oil in lamps and for medicines.

Why Lamprey Matter to the Tribes

In the five-minute video below, some tribal elders share what makes lamprey special to the cultures of the Columbia Basin tribes and why they’re worth protecting. The video is an excerpt from the 25-minute film The Lost Fish.

Lamprey Harvest

Lamprey are usually caught by hand at places on the river where rapids and waterfalls force the lamprey to attach themselves to rocks to rest before attempting to move further upstream.

Pacific Lamprey Evolution and Biology

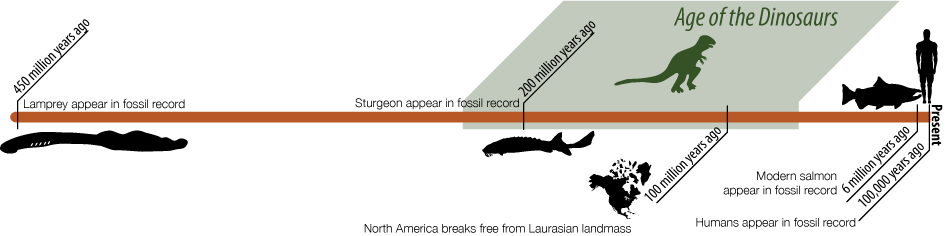

Pacific lamprey are one of the 40 members of the lamprey family still found on earth. The lamprey family is one of the oldest of all the vertebrates and is the only living representative of this ancient line. Lamprey have been on earth between 350 to 400 million years (compared to 200 million for sturgeon, 6 million years for salmon, and a minuscule 100,000 years for humans). They appeared during the same era as insects and seed-bearing plants.

Entosphenus tridentatus

The Pacific lamprey is distributed throughout the Pacific Rim from Japan to Mexico. Lampreys belong to a primitive group of fishes that are eel-like in form but lack the jaws and paired fins of true fishes. It is from this resemblance that they are sometimes called eels. (Click here to learn the differences between lamprey and eels.) Lamprey have a round sucker-like mouth, no scales, and breathing holes instead of gills. The Pacific lamprey is an ancient fish that has survived ice ages, mass extinctions, and shifting continental plates for hundreds of millions of years. Now, in less than a century, they have declined to the point where their very existence is in peril. The tribes of the Columbia Basin, honor-bound to protect them, are working to restore this important part of the ecosystem and tribal culture.

Lamprey Fossil

A lamprey fossil (Allenypterus montanus) from the Mississippian Era (~320 million years ago). This specimen was found in Fergus County, Montana. Due to their soft body parts, fossilized lamprey are extremely rare. Photo: fossilmall.com

Lamprey Lifecycle

After hatching from eggs, lamprey young, called ammocoetes, burrow in the mud and sand of freshwater streams. They are toothless and have only rudimentary eyes. The ammocoetes filter feed on microorganisms from five to seven years, after which they undergo a radical metamorphosis into adult lamprey. This metamorphosis includes rearranging the internal organs and the development of eyes and their characteristic toothed sucking disc. The adult lamprey then migrate to the ocean where they spend one to two years feeding before returning to fresh water to spawn. As adults in the marine environment, Pacific lamprey are parasitic and feed on a variety of prey. After spending one to three years in the marine environment, they cease feeding and migrate to freshwater in the spring. They are thought to overwinter and remain in freshwater habitat for at least a year before spawning the following summer. There is much that science does not know about these ancient creatures. Often treated as a “trash fish,” they have never been a priority for research. This has been changing, particularly due to the efforts of tribal scientists who are focusing their efforts and research on them in an effort to increase our understanding of the Pacific lamprey and give us as much information about them as possible in order to create appropriate and effective restoration plans to rescue this threatened species.

A major transformation

Lamprey are an Important Part of the Ecosystem

Due to their unique life history, the Pacific lamprey is an important component to the ecosystem both as a predator and prey. As a predator, Pacific lamprey has coevolved with native fish assemblages in the Pacific Ocean and freshwater ecosystems. As prey, lamprey is important to many species of fish, birds, and mammals, including humans. Like other anadromous fish species, they transport nutrients from the ocean to the freshwater environment.

Juvenile lamprey ammocoetes spend up to seven years filter feeding in the silt and gravel of stream beds. This behavior makes them particularly susceptible to pollutants and contaminants that settle out of the water.

The Threat of Extinction and Work to Restore Lamprey

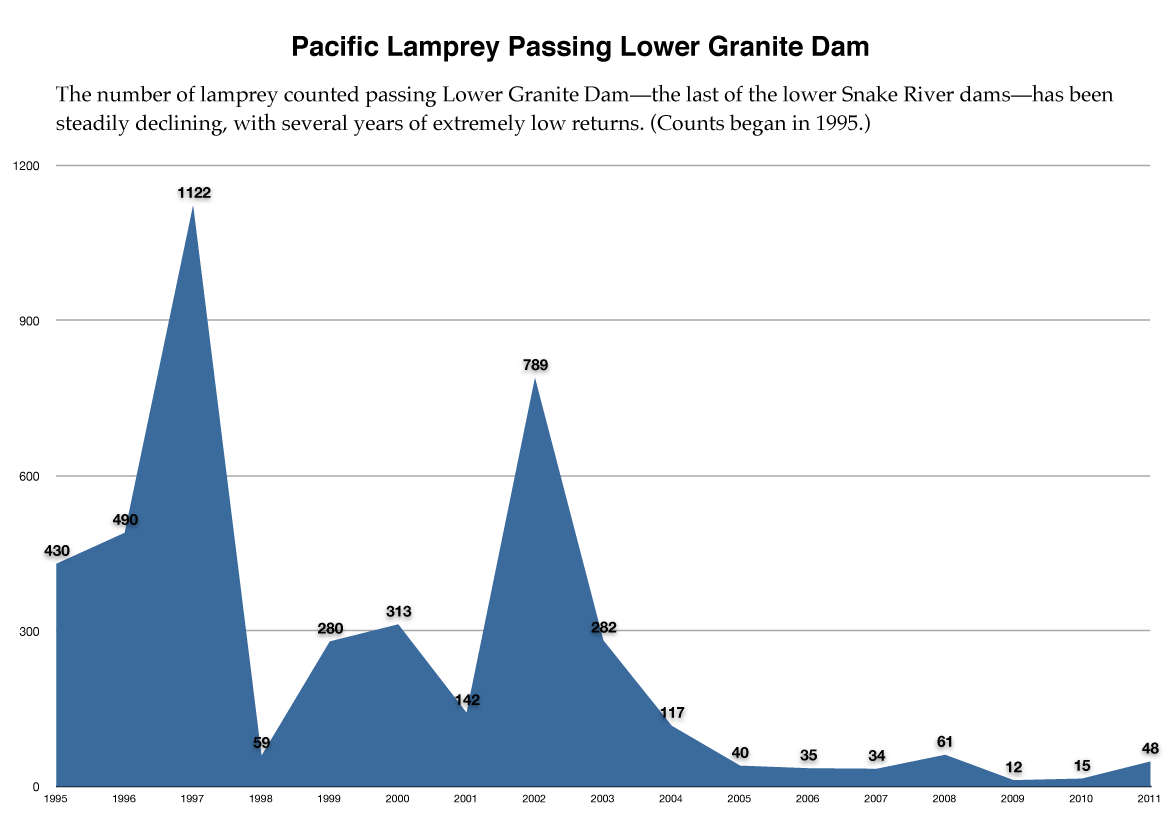

Similar to salmon, the lamprey lifecycle requires relatively pristine freshwater rivers and streams for spawning and rearing, mainstem river conditions conducive to migration to the ocean and back, and favorable ocean conditions. All three of these requirements have been degraded or impacted by human activity in the past 80 years, threatening the existence of this ancient creature. Counts of 400,000 adults were recorded at Bonneville Dam 60 years ago. Current counts are less than 20,000. The lamprey returning to Idaho face an ever more dire situation. In the past eight years, the number of lamprey passing Lower Granite Dam—the last mainstem dam before reaching Idaho—has been in the double digits. With this trend, the tribes are concerned that the lamprey in Idaho could soon go extinct unless something is done to reverse it.

“Here are my friends.”

The late Elmer Crow, Nez Perce, who dedicated the final years of his life to helping restore his “eels.” Here, he is showing a net full of Pacific lamprey at the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery awaiting outplanting into the wild streams and rivers in Idaho.

The number of lamprey counted passing Lower Granite Dam—the last of the lower Snake River dams—has been steadily declining, with several years of extremely low returns. (Counts began in 1995.)

In the past few years, the tribes have been the species’ primary advocates, calling for the protection and restoration of the Pacific lamprey. To address the lamprey’s decline, the Columbia River treaty tribes created the Tribal Pacific Lamprey Restoration Plan, the most comprehensive restoration plan for Pacific lamprey that the Columbia Basin has seen. Lamprey research, restoration projects, hydropower facility modifications, and policy creation are being performed by the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce tribes and their collective body the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.

Three lamprey summits have already been held, bringing together tribal, state, and federal agencies to address lamprey decline and ways to reverse the trend. The Tribal Pacific Lamprey Restoration Plan emerged from the efforts of the second lamprey summit, and marks the formal beginning of a coordinated, concerted effort by the region’s governments and agencies to protect and restore these fish whose ancestors swam the earth well before the lands that comprise the Columbia River Basin had even emerged from the primordial ocean.

Below are a selection of reports of this research, summaries from conferences, and responses that have come out of this work:

- Master Plan: Pacific Lamprey Artificial Propagation, Translocation, Restoration, and Research, 2018

- Synthesis of Threats, Critical Uncertainties, and Limiting Factors for Pacific Lamprey in the Columbia River Basin, 2017

- Framework for Pacific Lamprey Supplementation Research in the Columbia River Basin, 2014

- First International Forum on the Recovery and Propagation of Lamprey, 2011

Translocation

The tribes have taken an active approach to lamprey restoration, with efforts like this one where lamprey are being rescued from a dewatered fish ladder and outplanted in an upriver stream

A System Designed for Salmon