Working Towards Equitable Harvest

The Hard Work of Achieving Equitable Harvest

In the 1960s and 70s, two landmark court cases reaffirmed the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce tribes’ treaty fishing rights: U.S. v. Oregon and U.S. v. Washington. U.S. v. Oregon interpreted the tribal treaty fishing right to mean the tribes were entitled to a fair and equitable share of the salmon harvest and U.S. v. Washington ruled that a fair share meant half of the harvestable fish. These cases were a long, hard-fought, and often vicious battle between tribes and the states. The rulings created a need for the states and the tribes to agree on how many fish could be harvested each year as well as how to monitor their catches to ensure no one caught more than was allowed. Several factors make this job complex, including accurately predicting the run sizes, agreeing on appropriate overall harvest rates and allocations, and minimizing harvest impacts on threatened or endangered fish runs. Currently, mainstem fisheries are managed under a 10-year, U.S. v. Oregon Management Agreement that has provided stability for fisheries and improved harvest sharing.

Predicting Runs

It is impossible to exactly predict the size of a salmon run. Biologists have developed ways to forecast estimates, but these aren’t perfect. The methods have gotten better over time, but environmental factors both in fresh water and in the ocean can change and affect the survival and returns of adult fish. After approximately half of a run has reached Bonneville Dam, tribal, state, and federal biologists work together to update the actual run sizes. Run sizes are updated regularly throughout the middle and later parts of the run. Harvest rates are based on actual fish counts, not simply the pre-season forecasts. Larger runs have higher harvest rates, smaller runs have smaller harvest rates—so if a prediction is off, fisheries are adjusted to ensure they stay within the allowed harvest rate. This can result in either fisheries being restricted or in more fishing opportunity.

Fishery Timing

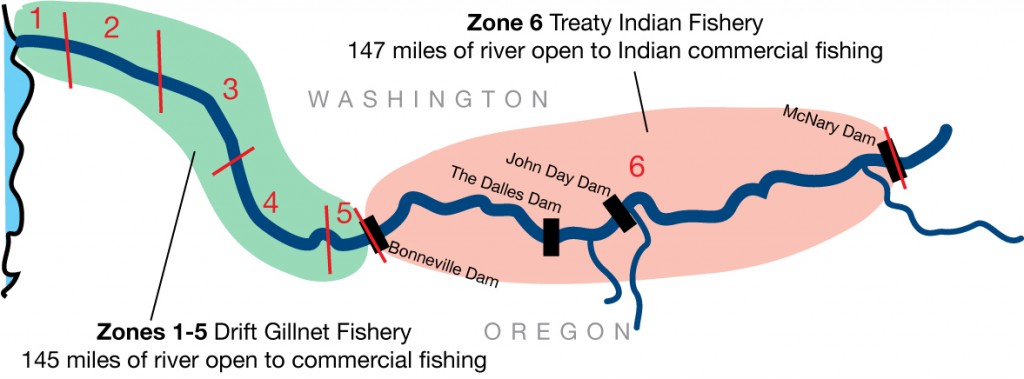

Depending on the time of year, it takes salmon anywhere from a week to a month to travel the 145 miles from the mouth of the Columbia River to Bonneville Dam. A large portion of the non-Indian fishery is in the lower river (Zones 1-5). Since the fish are in the lower river first, the non-Indian fisheries begin before many fish are caught by the Indian fishery in Zone 6 (the stretch of river between Bonneville and McNary Dams). A long-standing concern of many Indian fishers is the timing and size of non-Indian fisheries before many fish have passed Bonneville Dam. Fisheries managers have made some progress in dealing with this, but there is more work to be done. In spring fisheries, the states must manage for a run size 30 percent less than the pre-season forecast until the first run size update is made. This helps control the early season non-Indian fishing before much tribal fishing has occurred. In the summer season, the states allocate the majority of their share of the summer chinook to fisheries upstream from Zone 6. This means most of the summer chinook pass Zone 6 before they reach areas with significant non-Indian fisheries.

Fishery Coordination

As part of the court ruling, the U.S. v. Oregon parties (the United States, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and the four treaty tribes) were required to develop a system to equitably share their fisheries. It took twenty years of legal tests and negotiations to develop the first Columbia River Fish Management Plan in 1988. In 2008, the parties adopted a newer 10-year management agreement that defined hatchery production measures and harvest rates and allocations. The goal is to protect, rebuild, and enhance upper Columbia River fish runs while providing treaty Indian and non-Indian harvest. This agreement provides a framework for the tribal, state, and federal co-managers to conduct responsible, fair, and equitable fisheries. This co-management is evident leading up to and during each fish run. The tribes, states, and federal government are in close coordination monitoring each run as it develops, fine-tuning the models, adjusting the run size estimates, and tracking harvests. Sometimes coordination is weekly or even daily during the height of a run. Complex monitoring and evaluation programs also monitor the status of key natural-origin (wild) stocks to make sure the overall harvest is within allowed impact limits.

Different Fisheries, Different Priorities

Equitable Sharing of the Harvest

Protests

The Boldt decision that ruled tribes were entitled to half the salmon harvest enraged sport and commercial fishers. The decision sparked protests, some even burning effigies of Judge Boldt. Photo: Alaska Native News